Norse society, otherwise known as Vikings, was extremely patriarchal; however, like many other medieval European regions, women still played a crucial role in various aspects. The Viking Age covers the time period of 79-1050 CE and they inhabited the Scandinavian region which now includes Norway, Denmark, Iceland, and Greenland.[1] The discussion of what women in Viking society’s role really was is up for debate by many modern historians. This is because of the lack of contemporary narratives from the point of view of the Vikings themselves; therefore, scholars must rely on the perspective of the saga narratives to interpret what Viking history consisted of. Viking women played significant roles as wives and had an important influence on their husbands. This paper will examine the roles of two Viking wives and their experiences throughout the Vinland Sagas. To prove their positions, I will look at the general understandings that we have of Viking women’s roles in society, then I will examine two different voyages that the Vikings took across the Atlantic to Vinland, which there were women present on, and the experiences they faced over there. Specifically, I will focus on Freydis, the daughter of Erik the Red, and Gudrid, wife of Karlsefni. These women both became extremely well known throughout the Vinland Sagas for different reasons. Freydis was described as an ‘extremely haughty woman’ married to a ‘petty little man.’[2] Gudrid is described as close to a perfect Viking woman. These women respectively have earned their own reputations which proves that the situations of women may have been considerably less constrained than the surviving law books imply, highlighting the importance of considering the saga narratives.[3]

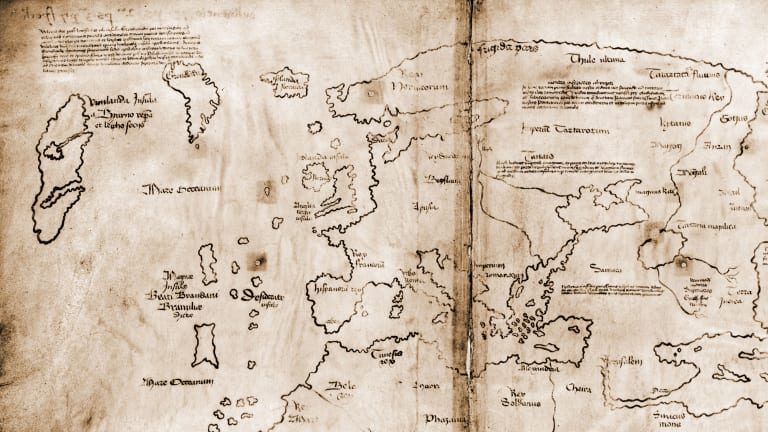

Viking sagas are an important resource into understanding the Scandinavian cultures but they differ from other primary sources. Sagas “were born in a cultural ferment where laws, genealogies, navigational details, historical events, origin myths, family stories, folktales, and poems were transmitted by word of mouth” but they were eventually recorded in these various sagas many years, or centuries later.[4] This paper will focus on the Vinland Sagas which includes two books: The Greenlanders’ Saga and The Saga of Erik the Red. Both of these sagas “tell of three successive voyages to North America by Norsemen from Greenland at the end of the tenth century.”[5] These sagas combine “probable fact and likely fiction in unverifiable proportions.”[6] As a result of the potential fiction involved in these sources, historians must approach them more skeptically than usual, making them significantly more difficult sources to work with. Due to political upheaval and the desire to expand their kingdoms, Vikings have been given more negative reputations that have forced them to be associated with bloodshed and death but, through the Sagas, we find that this is only part of the story.[7] The Book of Settlements details “One of the most formidable, dangerous voyages of the medieval Norse world [which] was the one that took the Norse west to Greenland, over the vast, turbulent waters of the North Atlantic.”[8] Greenland was settled by Erik the Red in the 980s, after he had been exiled from Iceland for his violence and fights.[9] The settlement of Vinland, modern day Newfoundland was completed by Erik the Red’s son, Leif. It was “after he ha[d] wintered and built some dwellings there, and grapevines are discovered, [that] he named the country Vinland.”[10] Two following voyages were completed by Karlsefni and his wife Gudrid, and Leif’s sister Freydis and her husband. Both of these voyages have slightly varying accounts in the two sagas but are important and influential to understanding Viking culture in different ways.

The Viking culture and beliefs vary significantly compared to other medieval European areas, and historian’s understandings of their culture is also made difficult due to the extraordinary nature of their Sagas. We are able to understand that “Viking women were bold and resourceful, determined to use their assets and skills to improve their material conditions, social status and political influence.”[11] This is seen through positions in their communities, or marrying for status. The various Viking sagas prove that “Norse mothers are neither saints nor monsters, but they are often cast as the enforcers of a rigid ideology that makes merciless demands on people for the sake of honour.”[12] The strictness of Viking legal codes greatly influenced the roles and responsibilities and how they were enforced on children from a young age so that they can grow up and successfully assume their duties. In contrast to modern perceptions of gender, “Carol Clover has argued that Viking Age societies possessed a ‘one sex’ perspective of gender that, instead of polarizing femininity and masculinity, equated masculinity with power.”[13] For this reason, what historians consider to be ‘warrior women’ could more accurately have been women pretending to be men, or taking on completely masculine tasks. There were also women that were able to hold power in terms of religion. Paganism was considered the dominant religion of the Viking colonies as it was not until later when Christianity reached Greenland. Abrams discusses that “there is no great narrative of conversion in Eriks Saga and Greenlanders’ Saga, they both show interest in the religious life of the early settlement, but with varying emphases and different detail.”[14] Women like Gudrid and Thjodhild, Erik the Red’s wife, played significant roles in the Christianity development in Greenland, after they both converted. These women are examples of how “women’s religious leadership and households that encompass different religious practices are both conventional tropes and credible circumstances”[15] With many Viking men stuck in the ways of paganism, the women appeared to be the ones that spread Christianity throughout Greenland. The Norse world eventually “began to abandon their traditional religion for the Christianity which was practiced by the superpowers of their day.”[16] Despite the potential exceptions to women’s assigned gender positions through religion or warfare, “the roles of men and women were nominally well defined by legal codes and social conventions and acting in a way deemed inappropriate to one’s sex resulted in significant social disapproval.”[17] There was an exception that allowed women, like Freydis, to speak and act out under the protection of her husband. Following a Viking siege in Paris in the 880s, an epic poem was written by a monk that details “Vikings’ wives goading their husbands and berating them for not fighting valiantly enough, and centuries earlier, Tacitus described women as bringing ‘words of encouragement’ to their husbands on the battlefield.”[18] Under the cover of their husband’s roles or titles, women were able to command and deceive, like Freydis did. The sagas allow historians to view narratives of what women’s lives were like but the challenge with these sources is that they only focus on prominent figures or families and leave out many mundane details of these women’s lives.

Freydis Eiriksdottir is mentioned in the Greenlanders’ Saga as being the daughter, or illegitimate daughter of Erik the Red. Despite her position being possible due to her marriage, and familial relations, due to her actions, Freydis earned her own title in The Saga of the Greenlanders: ‘The Prowess of Freydis, Daughter of Eirik the Red.’[19] She is described as having “Eirik’s ruthless and adventurous spirit reappear in [her],” and she “becomes joint leader of an expedition to Vinland the Good (in North America) around the year 1000. She displays a deviousness and cruelty to equal the major male players in the sagas.”[20] Freydis greatly contrasts what is mostly expected of Viking women and due to her aggressive levels of violence while in Vinland, she even fits the stereotype that Vikings were bloodthirsty monsters. In the Greenland Saga, Freydis threatens her husband with divorce if he does not avenge a fictious assault against her.”[21] This action proves Freydis’ cunning and manipulation. Even though her position on the voyage is connected to the men on the ship, she uses her deceitfulness to get what she wants. The following will briefly summarize the events of Freydis’ voyage. The start of Freydis’ story begins with her seeking out the two brothers from Iceland, Helgi and Finnbogi to see if they would accompany her to Vinland and share whatever profits they achieved. When they agreed, Freydis was lent her brother Leif’s houses in Vinland.[22] Once in Vinland, Freydis forced the brothers to build their own houses for their men while she stayed in Leif’s houses.[23] Later, she went to the brothers’ house and asked Finnbogi if they could trade ships, to which he agreed; however, when she returned home, she told her husband, Thorvard, that “‘[she] went to ask the brothers if [she] could buy their ship as [she] wanted a bigger one and this made them so angry that they beat [her] and treated [her] abusively’” then she threatened Thorvard with divorce if he did not avenge her. To this he “ordered his men to get up right away and fetch their weapon.”[24] Freydis had each man killed but “no one wanted to kill [the women]” so she “attacked all five women and left them dead.[25] After this terrible deed, they returned to their own, and it was only too clear that Freydis though she had acted very cleverly.”[26] When they left Vinland, Freydis had sworn her men to secrecy as they were “reddened by the blood of their countrymen” but the “gory tale comes to light, extracted from Freydis’ shipmates under torture” by her brother Leif.[27] Leif stated: “‘I can’t bring myself to deal with my sister Freydis as she deserves…but I prophesy that their descendants will never thrive,’” and according to the Sagas, Freydis’ descendants were all thought poor of.[28] This violent betrayal appears to have been unexpected and unprovoked, highlighting Freydis’ temper and her own violent nature but, because we do not have a firsthand account from Freydis, or any of her men, it is impossible to know just how the bloodshed actually went down. This was not the only tale of Freydis’ warrior abilities. Freydis also had a reputation of being able to stand against the skraelings, the native Americans in Vinland. While I could not find the excerpt in the Sagas themselves, Fridriksdottir describes a pregnant Freydis “berat[ing] the fleeing men for their unmanliness, declaring that if she had a sword, she’d fight, words which are meant to spur the men on to action.” This response comes as Freydis and her men are fleeing the Skraelings and “realizing that she is out of options, she turns to face them…She sees a sword lying by one of the bodies, and, snatching it up, she takes her bare breast out of her tunic and slaps it on the blade” which has a startling affect on the natives who then paddle away.[29] While this action seems quite unbelievable, with Freydis’ other actions, it may not be far off. There are some beliefs that “the act of slapping the sword on her bare breast could be a detail borrowed from Classical narratives about the Amazons, a tribe of warrior women who famously removed their breasts so as to be able to carry shields, throw javelins and shoot from bows.”[30] By comparing Freydis to these women, it not only crosses continental borders, but it again shows her status as a potential warrior woman, who would also be the first of her kind in North America. Fridriksdottir argues that “the portrayal of Freydis hovers somewhere between fascinated admiration and fear, even repulsion, of her violent femininity.”[31] This is proven through her status as a wife, and mother but also her cunning mind that allowed her to commit these feats of defiance and carnage.

Compared to Freydis, Gudrid played a much more religious role as a wife than a warrior one, but she was still significant in their voyage to Vinland. Gudrid was a wife, leader, traveller, mother, and Christian and was what the Viking woman embodied.[32] Gudrid’s first mentions in the sagas has to do with her religious role in the community, despite her position as a devout Christian, she was also raised with some paganism practices. Abrams discusses how “the sagas show a particular interest in religious oppositions. Gudrid’s dramatic dilemma in Eiriks saga—whether to help the community by performing the pagan rituals or remain true to her Christianity—is one.”[33] When there was a dilemma in the community and the pagan seeress needed help, Gudrid was recruited, to which she said “‘I’m neither skilled in magic nor a prophetess, but Halldis, my foster-mother in Iceland, taught me chants that she called vardlokkur’” but also that she had no intention in participating in this ceremony because she was a Christian woman.[34] Despite this, Gudrid did assist in the ceremony showing her loyalty to the community and the tensions between religions in Greenland at this time. Like Freydis, Gudrid also accompanied her husband to Vinland. Their voyage occurred prior to Freydis’ and despite the issues with the Skraelings as well, was much less eventful. After the first winter, Gudrid “gave birth to a boy whom they named Snorri.”[35] This birth made Gudrid the first known European to give birth on the North American continent.”[36] This was a significant chapter in the Viking Era, and was not without it’s own curiosities. One day, “Gudrid was sitting just inside the doorway beside her son Snorri’s cradle. A shadow darkened the doorway and in came a woman wearing a black tunic with a ribbon around her light chestnut hair. She was rather short and pale and had the largest eyes ever seen in a human head.”[37] This woman, who also claimed to be called Gudrid, did not say anything besides her name and vanished following “a great outburst of noise” at the same time that “a Skraeling was killed by one of Karlsefni’s men for attempting to make off with some of their weapons.”[38] Interestingly, the saga does not talk about this woman again or what she wanted and why she was also called Gudrid. Shortly after these events, Karlsefni suddenly spoke that he wanted to return to Greenland, so they did.[39] Karlsefni eventually died and “the management of the farm was taken over by Gudrid and her son, Snorri…When Snorri married, Gudrid left Iceland and traveled on a pilgrimage to Rose. On her return, she stayed with Snorri, who by then had built a church at Glaumbaer. Afterwards, Gudrid became a nun and anchoress, and remained there until she died.”[40] There are many questions about the validity of Gudrid’s stories in the Sagas and her position as a Christian woman, but overall, Gudrid represents a moral woman who did her responsibilities with her husband, and as a mother, and potentially used her widowhood to further her position within her religion

Knowledge about Viking Era society is very limited and historians are forced to rely on potentially fictionalized reports from the various sagas, or needing to incorporate other disciplines in order to truly understand the roles of Vikings. A modern obsession involving the recognition of Scandinavian heritage since the Victorian Era has romanticized Vikings with “individuals desir[ing] Viking ancestry.”[41] This idea has sparked interest in modern audiences to find out more about Vikings and has led to medievalism shows like Vikings. The Vinland Sagas feature fantastical tales of voyages to modern day Canada and close encounters with the Indigenous populations. Potential fictionalized narratives within the sagas contribute to a complicated ideal of what Viking lives were like. The challenge of trying to construct a historical narrative of Freydis and Gudrid’s lives is caused by missing firsthand accounts, and the bias made by the recorders of the sagas whom may have just wished to write a good story. Women played a small role in these trips but their ability to even participate on these voyages was rare and gave them a privileged position in society. What they then did with this position then determined the mark they left in the sagas. Freydis was a manipulative woman who was not afraid of using violence to get her way; whereas Gudrid was as close as could be to the idealized Viking woman. These voyages overseas were also trailblazing in their own right. At the time that Leif, and his successors set off, “Norse Greenland was in its infancy, barely a couple decades old. Leif, Gudrid, Karlsefni, and Freydis were amongst the first tough, hardy shoots of a society that would spring up from the icy soil and thrive for several hundred years.”[42] The various roles played by Viking women in their communities create an endless discussion for historians to examine, and Freydis and Gudrid represent a small portion of one location and one collection of sagas. There are countless other women mentioned in the sagas that play similar, or vastly different roles within their own communities.

Bibliography

“Chapter 10: Into the Western Ocean: The Faeroes, Iceland, Greenland, and Vinland” in The Viking Age: a reader. Edited by R. Andrew McDonald, Angus A. Somerville. University of Toronto Press, 2014.

“Chapter 4: Gender in the Viking Age” In The Viking Age: a reader. Edited by McDonald, R. Andrew; Angus A. Somerville. University of Toronto Press, 2014.

Abrams, Lesley. “Early Religious Practice in the Greenland Settlement.” Journal of the North Atlantic 2, (2009): 52-65.

Arneborg, Jette. “Norse Greenland: Reflections on Settlement and Depopulation” in Contact, Continuity, and Collapse: The Norse Colonization of the North Atlantic. Edited by James H. Barrett Brepols Publishers n.v., 2003.

Barnes, Gerladine. “Vinland the Good: Paradise Lost?” Australian and New Zealand Association of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 12, no. 2, (January 1995): 75-96.

Barraclough, Eleanor Rosamund. Beyond the Northlands. Oxford University Press, 2016

Ellis, Caitlin. “Remembering the Vikings: Violence, Institutional memory and institutional memory and instruments of history.” History Compass 19, (2020): 1-14.

Frank, Roberta. “The Greenlanders’ Saga by George Johnston.” University of Toronto Quarterly 46, no. 5, (Summer 1997): 488. (Review)

Fridriksdottir, Johanna Katrin. Valkyrie: The Women of the Viking World. Great Britain: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020.

Raffield, Ben. “Playing Vikings: Militarism, Hegemonic Masculinities, and Childhood Enculturation in Viking Age Scandinavia.” Current Anthropology 60, no. 6, (December 2019): 813-835.

[1] Ben Raffield, “Playing Vikings: Militarism, Hegemonic Masculinities, and Childhood Enculturation in Viking Age Scandinavia, Current Anthropology 60, no. 6 (December 2019): 813.

[2] Eleanor Rosamund Barraclough, Beyond the Northlands, (Oxford University Press, 2016): 137.

[3] R. Andrew McDonald, Angus A. Somerville, ed., “Chapter 4: Gender in the Viking Age” in The Viking Age: a reader, (University of Toronto Press, 2014): 85.

[4] Eleanor Rosamund Barraclough, Beyond the Northlands, (Oxford University Press, 2016):31

[5] Roberta Frank, “The Greenlanders’ Saga by George Johnston,” University of Toronto Quarterly 46, no. 5 (Summer 1997): 488.

[6] Geraldine Barnes, “Vinland the Good: Paradise Lost?” Australian and New Zealand Association of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 12, no. 2 (1995): 76.

[7] Ben Raffield, “Playing Vikings: Militarism, Hegemonic Masculinities, and Childhood Enculturation in Viking Age Scandinavia, Current Anthropology 60, no. 6 (December 2019): 813.

[8] Eleanor Rosamund Barraclough, Beyond the Northlands, 95.

[9] James H. Barrett, ed. “Norse Greenland: Reflections on Settlement and Depopulation” by Jette Arneborg in Contact, Continuity, and Collapse: The Norse Colonization of the North Atlantic, (Brepols Publishers n.v., 2003): 163.

[10] Geraldine Barnes, “Vinland the Good: Paradise Lost?” Australian and New Zealand Association of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 12, no. 2 (1995): 85.

[11] Johanna Katrin Fridriksdottir, Valkyrie: The Women of the Viking World, (Great Britain: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020): 13.

[12] Johanna Katrin Fridriksdottir, Valkyrie: The Women of the Viking World, 119.

[13] Ben Raffield, “Playing Vikings: Militarism, Hegemonic Masculinities, and Childhood Enculturation in Viking Age Scandinavia,” Current Anthropology 60, no. 6 (December 2019): 820.

[14] Lesley Abrams, “Early Religious Practice in the Greenland Settlement,” Journal of the North Atlantic 2, (2009): 58.

[15] Lesley Abrams, “Early Religious Practice in the Greenland Settlement,” 61

[16] Lesley Abrams, “Early Religious Practice in the Greenland Settlement,” 52

[17] Ben Raffield, “Playing Vikings: Militarism, Hegemonic Masculinities, and Childhood Enculturation in Viking Age Scandinavia,” 820.

[18] Johanna Katrin Fridriksdottir, Valkyrie: The Women of the Viking World, (Great Britain: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020): 78

[19] R. Andrew McDonald, Angus A. Somerville, ed., “Chapter 4: Gender in the Viking Age” in The Viking Age: a reader, (University of Toronto Press): 93.

[20] R. Andrew McDonald, Angus A. Somerville, ed., “Chapter 4: Gender in the Viking Age” in The Viking Age: a reader, 93.

[21] Ben Raffield, “Playing Vikings: Militarism, Hegemonic Masculinities, and Childhood Enculturation in Viking Age Scandinavia,” Current Anthropology 60, no. 6 (December 2019): 820.

[22] R. Andrew McDonald, Angus A. Somerville, ed., “Chapter 4: Gender in the Viking Age” in The Viking Age: a reader, (University of Toronto Press, 2014): 93

[23] R. Andrew McDonald, Angus A. Somerville, ed., “Chapter 4: Gender in the Viking Age” in The Viking Age: a reader, 93.

[24] R. Andrew McDonald, Angus A. Somerville, ed., “Chapter 4: Gender in the Viking Age” in The Viking Age: a reader, 94.

[25] R. Andrew McDonald, Angus A. Somerville, ed., “Chapter 4: Gender in the Viking Age” in The Viking Age: a reader, 94.

[26] R. Andrew McDonald, Angus A. Somerville, ed., “Chapter 4: Gender in the Viking Age” in The Viking Age: a reader, 94.

[27] Eleanor Rosamund Barraclough, Beyond the Northlands, (Oxford University Press, 2016): 137

[28] R. Andrew McDonald, Angus A. Somerville, ed., “Chapter 4: Gender in the Viking Age” in The Viking Age: a reader, 95.

[29] Johanna Katrin Fridriksdottir, Valkyrie: The Women of the Viking World, (Great Britain: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020): 117.

[30] Johanna Katrin Fridriksdottir, Valkyrie: The Women of the Viking World, 118.

[31] Johanna Katrin Fridriksdottir, Valkyrie: The Women of the Viking World, 119.

[32] Johanna Katrin Fridriksdottir, Valkyrie: The Women of the Viking World, 73.

[33] Lesley Abrams, “Early Religious Practice in the Greenland Settlement,” Journal of the North Atlantic 2, (2009): 61.

[34] R. Andrew McDonald, Angus A. Somerville, ed., “Chapter 4: Gender in the Viking Age” in The Viking Age: a reader, (University of Toronto Press, 2014): 54.

[35] R. Andrew McDonald, Angus A. Somerville, ed., “Chapter 10: Into the Western Ocean: The Faeroes, Iceland, Greenland, and Vinland” in The Viking Age: a reader, (University of University Press, 2014): 317.

[36] Eleanor Rosamund Barraclough, Beyond the Northlands, (Oxford University Press, 2016): 136.

[37] R. Andrew McDonald, Angus A. Somerville, ed., “Chapter 10: Into the Western Ocean: The Faeroes, Iceland, Greenland, and Vinland” in The Viking Age: a reader, 317.

[38] R. Andrew McDonald, Angus A. Somerville, ed., “Chapter 10: Into the Western Ocean: The Faeroes, Iceland, Greenland, and Vinland” in The Viking Age: a reader, (University of University Press, 2014): 318.

[39] R. Andrew McDonald, Angus A. Somerville, ed., “Chapter 10: Into the Western Ocean: The Faeroes, Iceland, Greenland, and Vinland” in The Viking Age: a reader, 318.

[40] R. Andrew McDonald, Angus A. Somerville, ed., “Chapter 10: Into the Western Ocean: The Faeroes, Iceland, Greenland, and Vinland” in The Viking Age: a reader, 319.

[41] Caitlin Ellis, “Remembering the Vikings: Violence, Institutional memory and instruments of history” History Compass 19, (2020): 7.

[42] Eleanor Rosamund Barraclough, Beyond the Northlands, (Oxford University Press, 2016): 140.

Writing Details

- Kendall Halfnights

- 17 June 2022

- 4335

- Viking Map of Vinland Voyage: https://www.passagemaker.com/trawler-news/the-myth-and-mystery-of-the-vinland-map

- Tweet

Leave a Reply