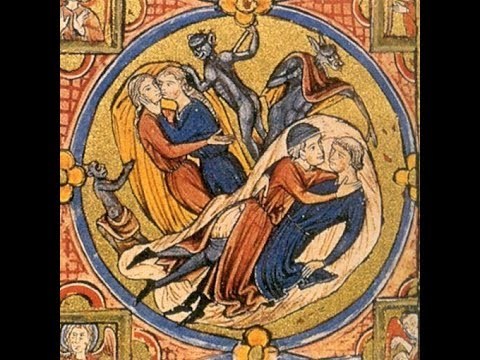

In Medieval women’s history, the sources and documents we have on them are scarce; this is much amplified for minority women in this time period. This is especially the case when attempting to discover more about the lives of queer women and trans women. The biggest hurdle is that women were seen as needing a husband, and their primary purpose in life was to serve as a wife and a mother. This idea of men being such an essential part of a woman’s life in order for her to find happiness is still ingrained in our society as we see many people still struggle with compulsory heterosexuality. Unfortunately, our primary sources of queer and trans women’s lives are provided through hostile sources such as court cases. Hostile sources paint these women and their experiences in negative ways in an attempt to justify why they were seen as criminals and received such harsh punishments. In relation to this, we never see the perspectives of these women and how they describe their feelings. It is important to consider so because many people in today’s society could understand how for them living their authentic life was worth the risk of prosecution. Women had an arguably easier time crossing gender boundaries and displaying masculine qualities than men did displaying female attributes. This is because men were considered superior, and it was shameful to behave as the inferior gender. It was even expected women would be curious to explore life as a man without societal restraints and lesser treatment. Men being more punished for having female qualities than women having male qualities is another reason we lack sources for trans and queer women. During this time period, it is also challenging to label someone as a lesbian or transgender because those are more recent terms. Only recently, society stopped thinking black and white about gender and sexuality. The medieval times will, of course, have different social and cultural norms from us that sexualities become hard to interpret today. There are many barriers to finding documents on the lives of trans and lesbian women, and the barriers are all connected to the patriarchy.

Women’s happiness in this time was centered around being a wife and mother. A woman was deemed successful if that was the life she led. This causes women’s history to brush over lesbianism (Bennett 2010). All women were assumed to have desires of having a husband and motherhood; nuns were pitied for “giving up” the apparent joys of heterosexual sex and motherhood. Historians wrote about peasant women always assuming they were heterosexual maidens, wives, or widows, emphasizing men being in their life romantically somehow (Bennett 2010). For intersex and transgender individuals, they were unable to bear children, something a husband could divorce over. In the case of d’Emparies he petitioned the court to have his marriage to Berengaria annulled because she was unable to have sex. A surgeon discovered Berengaria was intersex possessing male and female parts, meaning she was not able to have sex and bear kids, what women were expected to do (DeVun 2021). The ingrained belief that women needed a man even led to the low amounts of evidence in court cases compared to male sodomy. Authorities assumed women did not have homoerotic desires and ignored lesbianism because their expectations in life were highly centered around men. The sources that provide evidence of transgender and lesbian lives are usually being prosecuted for something other than their sexual and gender identity. For example, Katherina Hetzeldorfer was charged for engaging in intercourse with another woman. The investigation focused on how they were able to embody a masculine role. This case most likely got attention because Hetzeldorfer and her companion were socially isolated, and rumours spread that Hetzeldorfer abducted her companion (Puff 2017). Hetzeldorfer could have remained assumed to be her companions’ husband had rumours not spread about her true feminine identity. In addition, there was a case where a woman disguised herself as a man for two years for her love of learning, she managed to keep her true gender a secret for two years in one of the most social settings, university, this suggests other medieval women motivated by same-sex love could have managed the same (Bennet 2010). Cases presented to the court were usually presented because of something besides the same-sex encounter.

A significant barrier in obtaining sources for trans and lesbian women is that most are hostile sources, negatively depicting their experiences. There are also no documents that contain their perspective of their lives, giving insight into how they felt in their feminine body as opposed to when they expressed masculinity. Sexual minorities are hard to find and are often traced to legal or religious persecutions. Women wrote less, especially for minority women therefore, their writings did not survive well (Bennett 2010). In Hetzeldorfer’s case, they were drowned in the imperial city of Speyer in 1477, a degrading punishment usually used against women (Puff 2017). This hostile source shows many ways where they considered Hetzeldorfer their assigned gender, female, even though nowadays we could make a strong argument that they fall under the transgender umbrella. The source considers them female, and we do not get the chance to see how Hetzeldorfer described their own gender identity. The legal document portrays Hetzeldorfer as a criminal receiving the death penalty and their sexual partner Mutter painting herself as a victim of a gender hoax to avoid execution (Puff 2017). In Berengarin’s case, we have another situation where we do not get any of her perspectives on being intersex diminishing her ability to procreate. The document focuses largely on how she had both traditionally masculine and feminine attributes but does not go into detail on the divorce, what happened in her marriage, or her feelings about the court case. (DeVun 2021). There is an importance of these sources having evidence that different genders and sexualities have always existed, and we are not seeing a “fad” today; instead, people are more comfortable expressing their authentic selves as there are many more queer safe spaces today than there were in the Medieval times.

Men were considered the superior gender, arguably making it easier for women to cross gender lines, especially in the Viking world. A man crossing gender lines was considered much more dishonourable, women could divorce their husbands for wearing women’s clothes. Some people even believed if a woman touched a weapon, it could cause it to be ineffective (Hartsuyker 2019). Femininity was more frowned upon because it was deemed as showing weakness. As long as women did not use any device that mimicked penises, their same-sex relationship was not considered fully sexual as little harm was done because no sperm was spilled (Bennett 2010). This demonstrates the belief that women could not feel pleasure without something resembling a man. Their relation not being seen as fully sexual because of lack of sperm also connects to men being considered the ones who provide human life with little acknowledgment of women’s bodies’ contributions. There are examples of women taking on positions of warriors and generals and being highly praised however, if there were to be a case of a man taking on the women’s duties of tending to the children and supporting their wife, it would be shameful for him. Though many had beliefs women would not be allowed to fight or take on leadership roles, there were approximately 30 graves discovered of Viking women (Hartsuyker 2019). The armor was very masculine, and one of the few things that didn’t get a distinct gender binary in which one was for men and one was for women. Women were able to push gender roles and try to gain leadership positions, though they may have been immediately dismissed, they did not face the same punishment men did for expressing themselves as the inferior gender. This affects our ability to discover facts about transgender women’s history because pushing gender boundaries was seen as a desire to no longer feel inferior. It is hard to draw the line where a woman may have been expressing unhappiness in her assigned gender. The patriarchy affected silence in many cases of transgender lives (Puff 2017).

It is difficult to label people in history’s sexuality or gender because there is no way for us to know for sure. It is essential to acknowledge the difference in social and cultural norms will differ from today as a means to avoid stereotyping, Western culture has long celebrated intense same-sex friendships (Bennett 2011). For instance, in the relationship between Elizabeth Etchingbiam and Agnes Oxentridge, Oxentridge had a wish for her to be commemorated with Etchingbiam resulting in a conjoined brass statue (Bennett 2011). This was typically done for married couples resulting in their relationship being coined “lesbian-like.” We cannot know if they expressed affection in sexual ways but cannot exclude lesbian-like. Lesbian-like can encompass “women whose lives offered same-sex love, women who resisted conventions of feminine behavior, and women who lived in circumstances that encouraged the nurture and support of women” (Bennett 2011). During this time period, there was no clear definition of what lesbian behavior is and what is contrary to those behaviors. Lesbian-like is a term to take the pressure off mislabeling a historical figure. This connects back to the scarce resources in lesbian history as a matter of the patriarchy because men being such an ingrained part of women finding happiness led to such strong compulsory heterosexuality that lesbians still struggle with today in a much more accepting society. Sources are extremely limited because it was assumed women had desires for a husband and motherhood, not even considering lesbianism, women did not have such terms to use for themselves. There was no place for them to write their feelings for women as opposed to men, not allowing us to understand their perspective.

In conclusion, queer women and transwomen’s history is scarce and hard to come by because of patriarchal ideas. Firstly, it has always been ingrained in our society that men are an essential part of a woman’s life, leading to heteronormative ideas that continue to exist today. Women’s lives in this time period were largely emphasized on being a mother and a wife, and lesbian lives failed to even be considered. Women such as nuns were seen to be sacrificing a heterosexual lifestyle, again assuming all women craved a lifestyle imposed upon them. The sources found on women’s gender and sexuality mainly consists of hostile sources. Hostile sources not only provide no perspective of the woman’s lives but also negatively present them in order to justify brutal and degrading punishments served to many of the women. However, these sources serve great importance because it is evidence trans and lesbian lives have always existed. In the Viking ages, we see women pushing gender norms by being involved in positions such as warriors and generals, women could push gender boundaries such as clothing more easily than men because men were seen as the superior gender, and men being feminine was them showing weakness. That then affects our abilities to find sources on transwomen and whether women showing masculine features were to gain more superiority or gender dysphoria. There is an importance to avoid stereotyping and labeling because we cannot guarantee whether those were the actual labels historical figures would have used today. Imposing sexuality as black and white during these times led to no clear way to know or understand what lesbian behaviour could have looked like in comparison to today. The knowledge of sexual minorities can help prove sexuality is not a choice and has never been a new thing. Many of the documents not providing the queer person’s perspective are unfortunate, especially because how they describe not feeling like themselves in a heterosexual marriage or in their assigned gendered body is likely similar to how queer women feel today. This provides evidence that the weight of someone not expressing their authentic selves comes with much weight and sadness. The strong barriers we face in finding sources for queer women’s history can all relate to patriarchal ideals that loudly existed in this time period.

References

Primary Source

Helmut Puff, “Female Sodomy: The Trial of Katherina Hetzeldorfer (1477)”, The Journal of Medieval and early modern Studies 30,1 (2000).

Somerville, A., & McDonald, A. Chapter Four: Gender in the Viking Age

Legal Document. In The Viking Age: A reader (pp. 138). essay, University of Toronto Press. (2020)

Secondary Sources

Leah DeVun, The Shape of Sex: Nonbinary Gender from Genesis to the Renaissance (2021)

Linnea Hartsuyker, Queer Asgard Folk (2019)

Judith Bennett, “The L-Word in Women’s History” in History Matters: Patriarchy and the

Challenge of Feminism (2010)

Judith Bennett, Remembering Elizabeth Etchingtian and Agnus Oxentridge (2011)

Katherine L. Jansen, “Sexuality in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Times: New Approaches to a Fundamental Cultural-Historical and Literary-Anthropological Theme.” Vol. 89, No. 2, pp.

461-463. University of Chicago Press. (2014)

Writing Details

- Tyra Hallgren

- 17 June 2022

- 2142

- https://uncrcow.tumblr.com/post/179114171134/how-was-homosexuality-treated-in-medieval-times

- Tweet

Leave a Reply